Place

ContributeOne of the streets included in Colonel William Light’s 1837 ‘Plan of the City’, South Terrace was named, as were Adelaide’s other main streets, by a Street Naming Committee of 12 prominent settlers.

South Terrace forms the southern boundary of the City of Adelaide, connecting East Terrace and West Terrace. Four north–south thoroughfares change name upon crossing South Terrace: they are, from east to west, Hutt Street/Hutt Road, Pulteney Street/Unley Road, King William Street/Peacock Road and Morphett Street/Sir Lewis Cohen Avenue. Until 1967 Morphett Street south of Grote Street was Brown Street and Pulteney Street south of Wakefield Street was Hanson Street.

The terrace terminates at West Terrace/Goodwood Road and East Terrace/Beaumont Road. South Terrace is bordered by the South Parklands comprising, from east to west, Tuttangga/Park 17, Wita Wirra/Park 18, Pityarrilla/Park 19, Kurrangga/Park 20, Walyo Yerta/Park 21 and Minno Wirra/Park 21 West.

Aboriginal associations

Prior to European colonisation, the ‘South Parklands’ was occupied by the Kaurna people. They camped in the area and used it for food harvesting, hunting activities and burials. Early settlers recorded conflict there between the Kaurna and other Aboriginal people who had come from the Encounter Bay region. Camping largely ceased in the 1860s when Aboriginal people were reportedly driven out of the locality by the ‘torching’ or ‘burning out’ of their shelters.

The beginnings of European settlement

Colonel William Light’s plan divided the land of Adelaide into ‘town acres’, of which 39 were along the northern side of South Terrace. Early purchases and construction suggest that this location, overlooking parklands and away from the bustle of the north and the northwest corner of the settlement, was seen as a desirable place to live. A few acres on the terrace were preliminary purchases made in England prior to the early migrants’ departure; most were bought at auction after the new settlers arrived. Thirty-five of the acres are listed as sold on Light’s ‘Plan of 1840’.

Four influential and wealthy colonists who purchased acres on South Terrace – Colonial Treasurer Osmond Gilles, South Australia Association co-founder and Colonial Secretary Robert Gouger, South Australian Company accountant Edward Stephens and John Barton Hack, then a merchant – were members of the Street Naming Committee and all but Stephens had a street named after him in 1837. Other prominent colonists to buy land on South Terrace included Colonial Chaplain Reverend Charles Beaumont Howard, coroner, magistrate and Protector of Aborigines Dr William Wyatt and John Hallett, a merchant and part-owner of the migrant ship Africaine.

The ‘Kingston Map of 1842’ shows several large stone houses on South Terrace and that two small streets had emerged between some subdivided acres. Other buildings were few, scattered and small.

The 1860s: Cottages, mansions and a hotel

Workers’ cottages

By the 1860s workers’ cottages had begun to appear, chiefly towards the western end of South Terrace. Heads of households included a clerk, bootmaker, painter, carpenter, blacksmith and farrier. Miss Senner ran a ‘Ladies School’ from one of the premises.

Mansions

Wealthy settlers were attracted to this quiet part of town and the 1860s saw some substantial homes erected here. They included Sunbury House (then numbered 143–44), which was built in 1860–61 for Thomas Sparnon and leased to Albion James Tolley who began his wine and spirit business in Currie Street in 1862. Tobacco manufacturer John Dungey built his first South Terrace home in 1863 at number 141. In 1882 he built another two-storey residence next door.

Further to the east, linen merchant William Sanders constructed ‘Waverly’ and its accompanying coach house in 1865. The bluestone buildings were designed by James MacGeorge and built by James Farr. A ballroom was added in 1890. Sanders and his business partner, Robert Miller, developed the firm Miller Anderson which operated in Hindley Street until 1988. Sanders also took up pastoral leases, including Curnamona and Canowie Stations in South Australia’s Far North. The following owner of Waverly, Thomas Richard Bowman, was also a pastoralist. In 1984 heritage-listed Waverly still occupied a town acre, with a garden of large mature trees, the original garden wall and outbuildings.

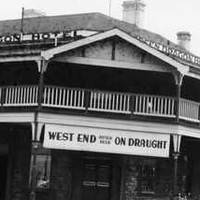

The Green Dragon Hotel

The first (and for decades the only) hotel on South Terrace was completed in 1858. The Green Dragon Hotel, on the western corner of Hanson Street, served teamsters and carriers servicing the city. It offered eight rooms, stables and stockyards. In about 1864 a weighbridge was constructed on the premises in accord with a new council by-law that required all wood, bark, hay, straw and coal to be weighed and certified by a licensed weighbridge. There was also a blacksmith shop and a wheelwright on the premises.

Subsequent modifications to the hotel included a two-storey northern extension in 1891 and a two-storey northwest rear extension in 1898. A balcony was added in 1924 when the weighbridge was removed. A single-storey western addition was constructed in 1940. In 1989 further renovations were undertaken and the hotel was later repurposed as the City Park Motel, with extra accommodation added over its western driveway, and in the first decade of the twenty-first century it was converted to a fast food business.

The Dragon Brewery to the west of the hotel operated until 1901, and the site was then used by other businesses.

The southern side of the terrace

From the 1850s to the 1870s the European settlers used the South Parklands for grazing livestock, collecting firewood and stock agistment. Community use was curtailed briefly in 1859 when a training area for militia volunteers was created in the western sector, but the rifle shooting and archery practice led to local protests and was soon stopped.

Duryea’s panorama of 1865 shows the South Parklands denuded of vegetation apart from fenced shelter belt tree plantations edging some roads. Post and wire fencing and tree planting began in the 1860s under City Gardener William O’Brien.

The 1870s: a residential street

The Australasian Sketcher of 1875 and the Illustrated Sydney News of 1876 show more construction along South Terrace. Larger buildings are clustered near East Terrace, while smaller homes and workers’ cottages are concentrated around the centre and the west. The South Terrace Railway Station was on the southwest corner with Peacock Road.

Directories for the period show South Terrace as a residential area. The only businesses were a dairy, the Dragon Brewery and the Green Dragon Hotel, all on or near the corner of Hanson Street. Thirty-three households in detached residences were listed on South Terrace east of King William Street.

South Terrace was more densely settled west of King William Street. Fifty-three households occupied dwellings, including four sets of terraces and row cottages. Heads of households worked in a mix of professional, white and blue collar occupations.

Social stratification in the 1880s

The stratified residential character of South Terrace is evident in the Book Plan of 1880. Between East Terrace and Hutt Street substantial dwellings sit well back from the street on large blocks. The pattern of construction is similar up to King William Street, with the variation of some slightly smaller buildings adjoining each other. To the west of King William Street semi-detached and terraced housing becomes more common, and the size of the dwellings reduces from medium to small.

The occupations of the residents confirm differences in social status and income along the terrace. The 50 occupations listed for South Terrace east are largely white collar, professional and business. They include seven merchants and manufacturers, two professors of music and two pastoralists. Murray River trader Edward Robert Fitzgerald lived here, as did solicitor and prominent Adelaide businessman Alexander George Downer (1839–1916). By 1886 the first private medical facility, Dr Gorger’s patient home, had been established. Francis Jane Whitby ran a Ladies Seminary from this sedate location.

South Terrace west was more densely populated and more diverse. Its 63 households included people in both blue and white collar occupations, but few wealthy employers. Labourers, coachbuilders, a barman and gardener mingled with a broker, clerk, detective and civil servant. The area also housed Mrs Ive’s Ladies School and a denominational ladies college.

A notable resident of South Terrace west was Charles Hill (1824–1916). Hill painted ‘The proclamation of South Australia, 1836’ more than 20 years after the event: indeed, he included people who were present at the time and some who were not. He became the art master at St Peter’s College at Hackney and ran an art school in Pulteney Street. The first meeting of South Australian Society of Arts was held at his home.

One explanation for the east–west social divide is suggested by the Book Plan, the compilation resulting from a survey of the city in preparation for the construction of a comprehensive sewerage system. Prior to the 1880s sewerage from South Terrace was conveyed by a drain across the parklands to the western corner of Greenhill Road and Unley Road where it percolated through the ground. South Terrace west was also closer to West Terrace Cemetery and the Bay Road to and from Glenelg.

South Terrace in the early twentieth century

The character of South Terrace continued to change in the first decades of the twentieth century. While it remained a predominantly a residential street, population density rose as the odd vacant lot was filled in and large establishments converted to boarding houses, health facilities and community centres.

By 1915 the Narma Nursing Home, YMCA Clubhouse and several boarding houses occupied previous homes on South Terrace east. Near East Terrace several mansions remained, but others were vacated as their wealthy owners moved away. Occupants were nevertheless from mainly white collar, business, pastoral and professional backgrounds. Some prominent figures such as Sir Jenkin Coles, Lady Brown and Professor Osborn, a botanist, continued to reside there. Coles, a member of parliament from May 1875 until November 1911, was the speaker in the House of Assembly from 1890 until he lost his seat for being absent without leave. His residence was later the headquarters of the TPI Association.

The density of South Terrace west also swelled. The 83 households listed in the 1915 Directory occupied smaller and more closely placed dwellings than those located at the other end of the street. The work of the residents was also more varied and represented a broader cross-section of the city’s labour force. A hawker, tailor’s cutter, blacksmith, carter and boiler maker shared the street with an engineer, dentist, missionary, accountant, two chemists and a master mariner. Unskilled workers were few.

South Terrace west residents included Ebenezer Cooke, the commissioner of audit, the artists Charles Hill and GAJ Webb, Police Commissioner Colonel LG Madley, Miss EH Makereth and her South Terrace School of Music, and music professor TH Jones.

Things were also beginning to change in the South Parklands, prompted by the Adelaide City Council appointing August Wilhelm Pelzer as city gardener in 1899 and shifts in thinking within the council in the context of a large city population and increased traffic with surrounding suburbs.

At the same time as additional roads were cut through the South Parklands and others were re-aligned, the parklands began to be viewed as a place for community recreation. Subsequent improvements were beneficial to people living and working in the south of Adelaide, particularly the South Terrace residents.

Osmond Park (now Osmond Gardens in Wita Wirra/Park 18) was established between Hutt Road and Glen Osmond Road in 1906–08 to provide a place for public relaxation and entertainment. Named after Osmond Gilles, the park featured gardens, a rockery, lawns, bridges and seating. Band concerts were held there regularly in the 1910s. In November 1909 one of the two fountains from the Jubilee Exhibition Building on North Terrace was relocated to Osmond Park (but it is now in Rundle Mall.)

In the following decade tennis courts were built, two community bowling clubs with clubhouses and greens were constructed, and Lundie Gardens was established on the corner with Goodwood Road. The first plantings of wattle trees were made off Sir Lewis Cohen Avenue (Minno Wirra/Park 21 West) on Wattle Day, 31 August 1912. The Dardanelles Memorial Obelisk was erected in the Wattle Grove on 7 September 1915. It was moved to Lundie Gardens in October 1940.

The first of Adelaide’s public playgrounds was established in the South Parklands during this period. In 1918 Mayor Charles Glover volunteered personal funds ‘to promote the happiness and well-being of the children of the city’. Glover Playground, west of Unley Road, was opened by Governor Lieutenant-Colonel Sir Henry Galway on 19 December 1919.

The 1920s: a place for women

In the 1920s South Terrace remained a largely residential and quiet location, although the make-up of residents was shifting. By 1925 the street had become a sought after location for married and single women living independently in the city. Women were listed as primary occupants of 30 of the 68 homes or apartments on South Terrace east and of 27 of the 88 in the west. Unfortunately, the Directory does not show their occupations.

While South Terrace west stayed much the same residentially, the eastern section continued to diversify, especially towards King William Street. The number of apartments and guest houses grew. On 3 July 1921 the premises for Pulteney Grammar School (the relocated and renamed Pulteney Street School) were opened by Governor-General Lord Forster. Almost next door, the Excelsior Ice Cream Works began operating. The Deaf and Dumb Mission (later Institute), Quambi Hospital, and the Acacias Sanatorium and Rest Home joined Narma Hospital (the former nursing home) as non-residential activities on the terrace.

In the parklands opposite, additional tennis courts and a croquet ground and shelter provided more opportunities for recreation. Near the western end of the street the Princess Elizabeth Playground was opened on 17 September 1929 by Lady Mayoress Lady Bonython. Children living in the low income southwest corner of Adelaide particularly benefited from this development.

Conversion, demolition and construction: the terrace in the 1940s and 1950s

The number of apartments, flats and guest houses grew on South Terrace after the Second World War as large old houses were converted or demolished and new buildings erected. Women living independently were well represented amongst residents, including as owners or managers of guest houses and apartments.

The number of non-residential premises increased as the secluded South Terrace east location became home to health and welfare organisations. Quambi Hospital and the Deaf and Dumb Institute were joined by the South Terrace Private Hospital, the Red Cross, Torrens House Mothercraft Training School, the Home School and St Andrews Private Hospital. Two industrial firms, Adelaide Margarine Co. and Viner Transport Co. also commenced operation nearer to King William Street.

The 1960s: Short stays and non-residential pursuits

The character of South Terrace altered significantly by the mid 1960s. The western portion was dominated by flats, apartments and guest houses. Many of the flats were reserved for holiday makers visiting the city. The number of permanent residents had dropped to 70 and their lower paid occupations reflected a drop in the desirability of the area as a place to live. Occupants now included labourers, caretakers and machinists as well as small business people and professionals.

More businesses and associations occupied the remaining larger homes and newly constructed premises to the west. Recent arrivals included the Master Builders Association, the Australian Institute of Builders, the Small Homes Service, the National Fitness Council of SA, the Workers Educational Association, the National Council of Women, the Youth Hostels Association, Australian Co-operative Bulkhandling Ltd, Fortune Australia (advertising) and McConnochie’s Emporium.

Meanwhile, welfare and health services rather than businesses were coming to dominate to the east. The newcomers included the Adult Deaf and Dumb Society, the Young Deaf Adults Hostel, the Girl Guides Association, the Mothers’ and Babies’ Health Association (at Torrens House), the Royal South Australian Bowling Association, the Totally and Permanently Disabled Soldiers Memorial Club and the Legacy Club. Specialist medical offices and St Andrews Presbyterian Hospital with nurses quarters were a focus of activity. The 52 remaining houses and the Green Dragon Hotel were joined by flats, guest houses, two private hotels and the Travel Lodge Motel.

An important and popular addition to the South Parklands was Veale Gardens between Peacock Road and Sir Lewis Cohen Avenue. Initiated by Town Clerk Bill Veale, the gardens were opened in 1963. They still feature a greenhouse, fountains, a sunken garden and pond, a rose garden and a creek. Adelaide sculptor John Dowie created the sculpture of Pan for the fountain in the sunken garden.

Into the twenty-first century

Few houses remained on South Terrace at the end of the twentieth century. Small businesses and flats dominated the western end. Trade unions were strongly represented at Trades Hall near West Terrace, while employer organisations clustered further along. Nearer to the centre, the height of buildings had increased: a lone high-rise office block dominated the terrace’s northwest corner with King William Street.

South Terrace east retained individual residences towards East Terrace. St Andrews Hospital occupied a large area near the east end. Several large motels had been established between King William Street and Pulteney Street, and the Green Dragon Hotel converted to a motel and then to a fast food operation. Besides expanding to occupy several of the original town acres, Pulteney Grammar School had initiated a first for the city with a permanent elevated footbridge linking the north side of the terrace with the South Parklands. Associations, small business and medical related services intermingled along the terrace.

By the end of the century an additional garden had been established in the South Parklands. The Himeji Garden (or Garden of Tranquillity) was developed in the 1980s to recognise the link between Adelaide and one of the city council’s sister cities, Himeji in Japan. It was designed by Japanese architect Yoshitaka Kumada.

In the first decades of the twenty-first century South Terrace continues to provide a quiet location for small business, associations, welfare and health services and a few residences. But ongoing change is evident with premises like those of the South Australian Deaf Society, Legacy, the Mothers’ and Babies’ Health Association and the TPI (Totally and Permanently Incapacitated) Association SA being vacated by those organisations. While many old houses have gone, new construction is relatively small scale. The South Parklands attracts visitors to its gardens and sports participants to the courts, cycling facilities and sports grounds scattered throughout the area. Indeed, as a sign of continuity amidst change, in 2013 the Adelaide Harriers Amateur Athletic Club achieved its centenary – a year after it was formed in the North Parklands it had moved to the Victoria Park racecourse but since 1921 ‘the Harriers’ have been based in Kurrangga/Park 20.

Media

Add mediaBanner

Images

Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia, SLSA: B2725, Public Domain

Feature

Images

Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia, SLSA: B56810, Public Domain

Flats and Apartments

Images

Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia, SLSA: B11292, Public Domain

Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia, SLSA: B14416, Public Domain

Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia, SLSA: B10551, Public Domain

Mansions

Images

Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia, SLSA: B11292, Public Domain

Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia, SLSA: B10509, Public Domain

Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia, SLSA: B26668, Public Domain

Non-residential establishments

Images

Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia ,SLSA: B12500, Public Domain

Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia, SLSA: B7035, Public Domain

Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia, SLSA: B5101, Public Domain

Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia, SLSA: B4896, Public Domain

Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia, SLSA: PRG 280/1/31/127, Public Domain

The Green Dragon Hotel and Dragon Brewery

Images

Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia, SLSA: B8595, Public Domain

Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia, SLSA: B1838, Public Domain

Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia, SLSA: B2726, Public Domain

The South Parklands

Images

Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia ,SLSA: B32826, Public Domain

Worker’s Cottages

Images

Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia, SLSA: B5829, Public Domain

Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia, SLSA: B3949, Public Domain

CommentAdd new comment

Quickly, it's still quiet here; be the first to have your say!