Thing

ContributeDistinguished soldier, sailor, linguist, musician and painter Colonel William Light (1786–1839) the first surveyor-general of South Australia. Light commanded the brig Rapid for its voyage to the new colony. Reaching Kangaroo Island on 19 August 1836, Light immediately began to search for the most appropriate site for the colony’s capital. He had been given sole responsibility for choosing its location.

After considering various sites, including Port Lincoln and Encounter Bay, Light placed Adelaide a little inland from the sea on the banks of a river, which wound across a fertile plain from nearby hills. However, his choice was opposed by prominent figures, not least of whom was Governor John Hindmarsh who wanted the capital to be a port and therefore located at Port Lincoln, Port Adelaide or Encounter Bay. But Light persisted and won the day. He could see that his site gave best access to fresh water, minimised the threat of flooding and presented good ground on which to build, while still being close to a suitable harbour.

The site of Adelaide was fixed on 29 December 1836; Light had been too busy on this work to attend the reading of the proclamation the day before. On 11 January 1837 he began his survey of the capital. His plan for North Adelaide and South Adelaide (now the central business district) on either side of the River Torrens and surrounded by a belt of parklands, was completed by May of that year. Light’s Plan, with its grid layout of streets and squares, is the foundation and guiding framework of the City of Adelaide.

Colonel Light was also required to survey more than 2400km of the coastline and surrounding countryside, to divide 150 square miles (c. 390km2) of country into sections and to reserve areas for country towns. This huge task was expected to be completed within two months. Light found that he had insufficient staff and resources to undertake the work. Light and Resident Commissioner James Hurtle Fisher sent Light’s deputy, George Strickland Kingston, to England to request additional support. The South Australian Colonisation Commissioners in Britain not only rejected the request, but also insisted that trigonometry surveys be replaced by faster ‘running surveys’. If Light refused to do this form of survey, he was to be replaced by Kingston and relegated to other work. On 2 July 1838 Light resigned with all but two of his staff.

Light became a principal partner in the firm of Light, Finniss & Co. However, his health deteriorated rapidly and he was unable to continue working in the next year. His circumstances were not helped by a fire on the day after he ceased work: on 22 January 1839 at 2pm his hut and the Survey Office on North Terrace burnt to the ground. The fire had commenced in Fisher’s neighbouring residence, which it destroyed along with the Land Office. The Southern Australian of 23 January 1839 reported that various official records and maps in the offices were saved, but Fisher and Light

had to witness the total destruction of their houses, furniture, books … live stock … and, what is beyond all the rest, being irremediable, their private accounts and papers. Scarcely an article of any value has been saved by either party from the devouring element … amongst in Colonel Light's losses we must include several of his instruments, the whole of his valuable portfolios of drawings executed during his residence in Egypt and in the Peninsula, and what as colonists we yet more regret, the private journal he has diligently kept for the last 30 years. So rapid was the progress of the flames that the inmates in either residence had scarcely time to escape.

Despite his illness, Light recorded some of his life in the self-published A brief journal of the proceedings of William Light in May 1839. Nursed by his partner Maria Gandy, Light died of tuberculosis at his Thebarton home on 6 October 1839.

Light’s grave

In spite of being treated shabbily, some colonists refused to visit him in his final days because he and Maria were not married, William Light was genuinely mourned. His work as founder of Adelaide was recognised immediately. He was given the unique honour of burial in the city square bearing his name and granted South Australia’s first official public funeral. On the day of his funeral, shops were shut and public offices closed by order of Governor George Gawler, who had replaced Hindmarsh in October 1838.

On 10 October 1839 immediate friends and acquaintances assembled at his home to accompany the body to Trinity Church, North Terrace for the funeral service. At the ‘old Native Location’ the procession was joined by Gawler, all of the public officers and 423 male colonists. The procession following the undertaker was headed by Reverend Charles Beaumont Howard (the colonial chaplain) and other clergymen, Light’s colleagues, employees and friends, Light’s servants, the government officers, the magistrates and the sheriff, the Legislative Council, the colonial judge, the governor and his private secretary, and the ‘gentlemen, all in deep mourning’ who marched ‘two by two’. The procession joined more than 1000 colonists waiting at the church. Several thousand people assembled at the grave to pay their respects to Colonel William Light as his body was interred at midday.

Neo-Gothic monument

On the day of the funeral, a notice in the South Australian Register called friends of Light to a meeting to discuss the best means of erecting a lasting monument to him. The meeting was chaired by John Morphett and included explorer Captain Charles Sturt, Resident Commissioner James Hurtle Fisher, Colonial Secretary Robert Gouger and surveyor Boyle Travers Finniss, a close friend and business partner. A monument of white South Australian marble or a bronze statue from England were suggested as fitting memorials. The final choice would depend on the funds raised. Subscriptions were called and £250 was raised immediately, with the governor agreeing to allocate £100 from the public purse also.

But fundraising stalled as the colony went into economic recession. Further work on the proposal was suspended until some determined supporters took up the cause again. Appeals and a public concert finally generated enough money to proceed, although on a more modest basis.

The selected monument was designed by George Strickland Kingston and carved from sandstone. It comprised an elaborate Gothic cross, 13.7m high. The tall base was divided into three compartments: the lower comprised five tablets, reserved for inscriptions and Light’s coat of arms; the second consisted of five deep trefoil-headed niches, surmounted by gables with leaf-shaped Gothic decorations (crockets); and the third level featured open trefoiled arches, ornamented by tracery. The lower and second compartments were supported and further ornamented by decorative buttresses. The monument was topped by a spire, ornamented with crockets and the cross. The foundation stone was laid on 18 February 1843 and the cross carved by a Mr Lewis. The completed Gothic cross was erected in 1844.

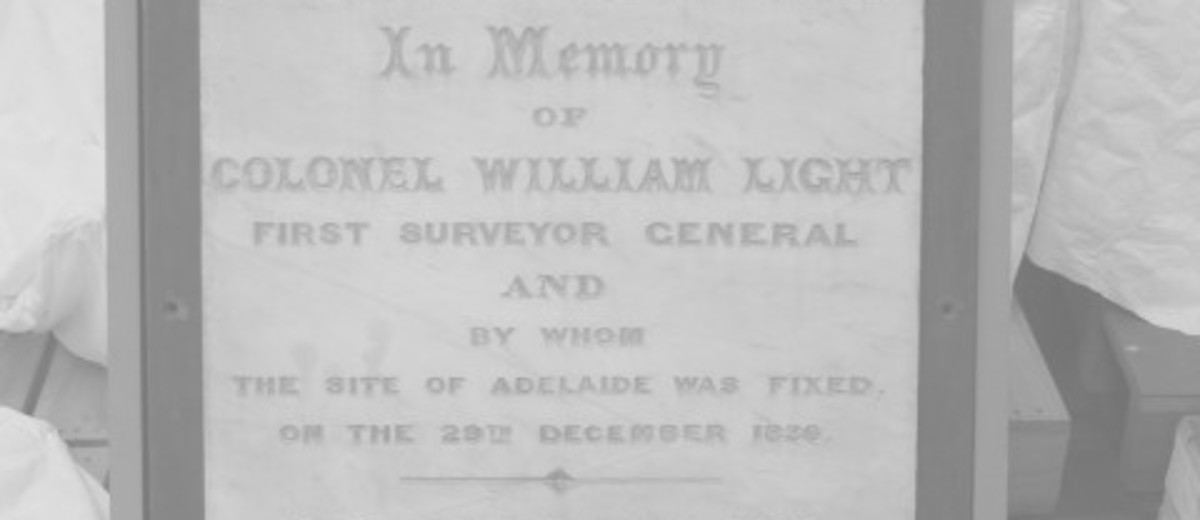

In 1876 the Adelaide City Council placed a white marble tablet on a panel of the monument: its inscription acknowledged the pioneers of South Australia for erecting the memorial to Light.

Granite monument with theodolite

By 1892 the monument was badly weathered and beyond repair. Mayor Frederick Bullock was determined to do something about it. He established a committee to erect a ‘substantial monument’ to Light. Initial enthusiasm generated public subscriptions of £348: Sir Henry Ayers donated £50, John Howard Angas £55 and Governor Kintore £25. The Adelaide City Council pledged £500. The government granted £1000 after Dr George Mayo offered a self-portrait of Light to the Art Gallery of South Australia on condition that it allocate substantial funds to the project. Agent-General Sir John Bray in London also collected subscriptions. However, by this time the colony was in another severe economic depression, with bank failures and widespread unemployment. The government reneged on its promise. The committee and a proposed design competition lapsed.

Twelve years later a meeting of subscribers sent a new deputation to the state government for financial support. This time they met with success. Funds were transferred to the Adelaide City Council and another Colonel Light Monument Committee formed of representatives from subscribers, the government and the council. It was agreed to not only replace the monument on Light’s grave, but also to erect a separate statue in the city. A design competition generated proposals from 22 artists; 13 for the statue and nine for the memorial.

HL Jackman’s winning memorial design featured a bronze tripod and theodolite on a tall polished granite column of Murray Bridge red granite and a base of Monarto grey granite. Jackman was appointed architect-in-charge, with JJ Leahy contracted to erect the monument. AW Dobbie & Co. cast the bronze work, F Burmeister did the engraving and FH Herring polished the monolith.

Bronze plates on the southern and northern faces of the monument acknowledge the ‘People of South Australia assisted by the Government of the State and the Corporation of the City of Adelaide’ for their efforts to replace the monument erected by the pioneers in 1844 to the memory of Colonel William Light.

A plaque placed at the base by members of the Institute of Surveyors Australia, the South Australian Department of Lands and the Pioneers Association of South Australia is a tribute to Light as the founder of Adelaide, includes the well-known lines from A brief journal of the proceedings of William Light, where Light thanks his enemies for giving him the sole responsibility of choosing the site of Adelaide: ‘The reasons that led me to fix Adelaide where it is I do not expect to be generally understood or calmly judged of at present … I leave it to posterity … to decide whether I am entitled to praise or blame’.

The 1876 marble tablet was removed in 1905. It was renovated and mounted on slate, before being presented to the Public Library Board to be exhibited in the vestibule of the State Library. The tablet is now part of the State Historical Collection of History SA.

Unveiling

The new monument was unveiled on 21 June 1905 by Mayor Theodore Bruce, following an address by Deputy-Governor Sir Samuel Way. Premier Richard Butler and two senior ministers, Adelaide City Council aldermen and councillors, and members of the Colonel Light Monument Committee attended. Invited guests included 100 people who had arrived in South Australia prior to 1845. Some of them had witnessed Light’s funeral 66 years before. Thousands of members of the public were also present. Boys from Adelaide’s state schools provided a guard of honour and led the singing of the ‘Song of Australia’.

Light’s self-portrait in oils was finally presented to the Art Gallery by George Gibbes Mayo (son of Dr George Mayo, who had died in 1894) on behalf of the Mayo family.

The modern era

Each April the Adelaide City Council celebrates Light’s birthday. This tradition began in 1859 when four of the founders of the colony (Light’s friends George Palmer, Jacob Montefiore, Raikes Currie and Alexander Elder) presented the ‘Loving Cup’, a large ornamental silver bowl, made in England in 1766–77, to the mayor and the council and asked that the councillors ‘gather each year to toast Light’s health with South Australian wine’ (Adelaide City Council; Bulbeck, p263). From 2004 to 2011 a more elaborate ceremony, complete with theatrical performances, was held in Light Square. The gravesite and 1905 monument were upgraded with a pond and new pathways during 1985–86. The council also undertook a major refurbishment of the monument and the area surrounding it in 2008.

Media

Add mediaImages

History SA, South Australian Government Photographic Collection, GN05902.

History SA collection, memorial tablet, HT2001.168

History SA, South Australian Government Photographic Collection, GN05903.

Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia SLSA: PRG280_1_11_435, Public Domain

Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia SLSA: B 2367, Public Domain

Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia SLSA: PRG280_1_1_141, Public Domain

Comments

CommentAdd new comment

Not everyone felt that way at the time Kelly!

So from the date of choosing the site of Adelaide to the date of his resignation, his term in office was a year and a half. That was a Herculean effort on behalf of the good colonel.

Hi Kelly,

As I'm sure you'll appreciate we haven't included all details of Light's first month's in this article in which the author, Jude Elton, has focussed on the grave and monument. I checked with Jude, who referred me to her sources (see the 'learn more' section at the top right of the article). If you have references for your comments please do add them. We're always happy to have further information and contrasting interpretations.

Could you please correct this webpage.

"Reaching Kangaroo Island on 19 August 1836, Light immediately began to search for the most appropriate site for the colony’s capital."

Light was carrying out his duties in searching for the most appropriate site for a capital on his arrival in South Australian waters <before 19 August>. He ruled out the Encounter Bay coastline before reaching Kangaroo Island. Given the opposition that followed later overlooking this fact can mislead readers.

"This huge task was expected to be completed within two months. Light found that he had insufficient staff and resources to undertake the work. Light and Resident Commissioner James Hurtle Fisher sent Light’s deputy, George Strickland Kingston, to England to request additional support."

The planning and survey of the town of Adelaide's 1,000 saleable one-acre Town Sections was carried out with unprecedented speed for the time, taking less than two months. There cannot have been any expectation of Light completing the survey of the City and District of Adelaide (Adelaide Plain) in two months.

Light and Fisher did NOT send Kingston back to England. Kingston sought, and was given permission to leave, Light considering him virtually useless, Kingston having caused delay in the city survey of two weeks through Kingston's incompetence at basic mathematics and having no idea of the basic mathematical characteristics of the fundamental land parcel of the city - square one-acre sections.

Light estimated that his small survey team was sufficient for the initial exploratory surveys, but predicted (before his arrival in South Australia) that he would need additional resources once the detailed land survey (e.g. the survey of the Preliminary Country Sections of the District of Adelaide) commenced.

Light designed and pioneered an unprecedented co-ordinated cadastre for the Adelaide Plain, thereby expediting rapid re-survey based on trigonometrical survey, or triangulation. Expected to be the first of its type in the world. Using trigonometry, but not called a "trigonometry" survey.