Subject

ContributeFrom its inception recurring periods of high unemployment dogged the life of the fragile South Australian colony. Various recessions had been interspersed by brief periods of prosperity – especially during the copper ‘booms’, while an atypical inversion in the form of labour shortages occurred during the Victorian goldrushes of the early 1850s.

In response to yet another downturn in the early 1890s the government of Charles Cameron Kingston devised a plan of labour or village settlements. Kingston, an iconoclastic radical, saw in these schemes further possibilities of the kind of ‘state socialism’ much favoured by radical liberals of this time, such as the creation of a state bank. At least 13 labour settlements were located along the River Murray, including at Pyap, Ramco, Waikerie, Holder, Kingston, Moorook, Murtho, New Residence and Lyrup, with others at Mount Remarkable in the Far North and Nangkita.

The aim of these communities was to trial new forms of (collective) property ownership, make use of new (especially irrigation) technology and provide employment for the city-based unemployed. The radical Irish MP Michael Davitt was much taken by these endeavours during his 1893 Australian tour, regarding this ‘co-operative communistic plan’ a ‘most courageous action on the part of a state’.

The settlements were largely unsuccessful, partly due to the novel management arrangements envisaged – there was little precedent for cooperative ownership of property in the sturdy individualism of South Australia – but largely due to their being hastily conceived in terms of finances, structure, and vision. They had as a premise the then popular view that rural living can offer a healthy physical and moral life for the jaded city dweller. The improved economic fortunes after the 1890s depression meant there was little incentive for settlers to remain bound to their villages.

Following a royal commission, the system was officially abandoned and more traditional tenure arrangements on the sites were accompanied by the gradual establishment of the fruit and vine industry which is now the economic backbone of this part of South Australia.

Media

Add mediaImages

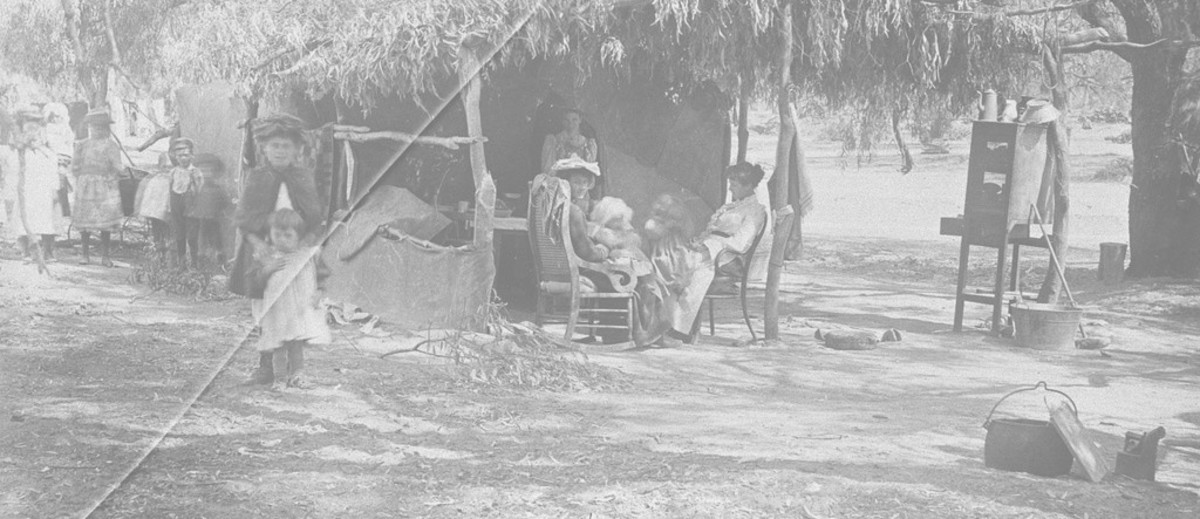

Image courtesy of State Library of South Australia, SLSA: D 2861/24(L), Public Domain

Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia, SLSA: B 62476, Public Domain

CommentAdd new comment

Quickly, it's still quiet here; be the first to have your say!