Event

ContributeOn 20 September 1855 violence erupted during the Legislative Council election when a mob attempted to interfere with the voting at West Adelaide. Later that day a full riot developed there after the close of the election, as a furious attack was made on the supporters of one candidate, Anthony Forster, editor and part owner of the South Australian Register newspaper. At that time the British colony of South Australia was ruled by a governor appointed by the British government. He appointed officials and made laws, and was advised by a small Legislative Council, whose members he nominated. Early in the 1850s the British government had allowed the election of members to the Legislative Council. This was a considerable move towards democratic rule in South Australia. A major task for the Legislative Council was to draw up a constitution for the colony. But how democratic should this new constitution be, and what form should it take? Who should be allowed to vote on the matter, and how? Should there be one or two houses of government, and should there be peers or freely elected men? These questions caused a lot of civic dispute and tension.

The election process to decide these matters also needed to be improved: there was limited franchise, voting was at public polling booths (generally in pubs) and men had no privacy or secrecy when voting so sometimes there was coercion and even violence. On the morning of the election on 20 September, reported the Register, a ‘very great’ crowd gathered at the Blenheim Hotel, Hindley Street to hear speeches by Forster and his opponent, James Hurtle Fisher. Forster supported the model of a freely elected Legislative Council, liberal voting rights for ordinary men as well as landowners and election by confidential ballot. The Register reporter said that the ‘utter insufficiencies’ of the Blenheim as a polling station ‘soon became painfully manifest’, as men were forced to record their votes outside the building, in full public view. As an eyewitness recalled in 1911:

Those were the days of open voting. The 'touters' standing at the door could see by the colour of the ballot-slip used which man the elector voted for, and they signalled the fact to the crowd, who were all eager partisans of one side or the other. This caused very bad feeling between the rival factions.

Intimidating behaviour at polling station

The Register reported that at the Blenheim a ‘premeditated and organised attempt to create a disturbance was patent to every observer … Groups of sturdy and desperate-looking men’ carrying cudgels lurked near the hotel. Some reports said these were Irishmen, and not electors, and it was thought their violent behaviour was to intimidate people against voting. A fight took place in the polling booth almost as soon as it was opened, and some blows were exchanged. At one point during the day the violence grew, even though there were 60 police constables stationed nearby. The Register complained that the police remained inactive while electors were being beaten and obstructed from voting. Frequent appeals were made to the Inspector in vain, as the Commissioner of Police said that he would not interfere until there was a riot in the street. Unknown to those at the Blenheim, the military had also been ordered in readiness close by, although ‘very prudently and properly concealed from public’.

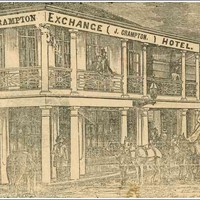

At the close of the polls, Forster had beaten Fisher by 740 votes to 604. The final result was announced by Forster’s supporters from the balcony of the Exchange Hotel, opposite the Blenheim. While Forster made a victory speech, ‘a number of riotous persons occupied the balcony of the Blenheim Hotel, from whence they yelled forth defiance at the party supporting Mr Forster’. Flags belonging to his supporters were ‘pulled down and torn to shreds with almost savage ferocity’. Then the gang ran into the street and charged the crowd, which included many women and children.

A mob storms the hotel

The mob took up a position in front of the Exchange Hotel, threw missiles at Forster’s men and then stormed the hotel:

a scene of great confusion and disgraceful violence followed, in which many inoffensive persons were seriously injured. Several persons scrambled out of the windows, over the balcony, and even by the roof of the Exchange Hotel, to escape from the shillelahs [clubs] and still more dangerous weapons of their ruffian assailants.

Finally the police commissioner acted, and the constables scattered the crowd, making several captures, although taking, as the Register commented, ‘none but the most outrageous’. In the fray, Constable Alexander Wright was severely injured, and some of the men arrested required medical assistance.

The Register lamented the violence and corruption of the day, hoping that the ‘disgraceful proceedings’ were at an end. Electoral irregularities meant that the result of the day’s vote was declared void, serving as a potent example of the need for electoral reform. The Register said that it was ‘painful to think that men who have had heretofore cause to complain of political coercion should themselves, in a land where all may vote freely, attempt by brute force to subvert freedom of election’. While there was no official explanation for the violence, or the refusal of the police to intervene for so long, the colonial secretary later chastised some government officers in private letters.

Aftermath

In the end, all but one of the 16 members elected to the Legislative Council in 1855 were supporters of the secret ballot, and it was duly included in the Electoral Act that followed the Constitution Act. How best to make the ballot secret was debated in February 1856. Victoria had adopted the secret ballot the previous month. South Australia borrowed the innovation of ballot papers printed with the names of candidates, but improved the Victorian system by not numbering papers. This meant that a vote could not be linked to a name on the electoral roll, thus ensuring absolute secrecy.

Media

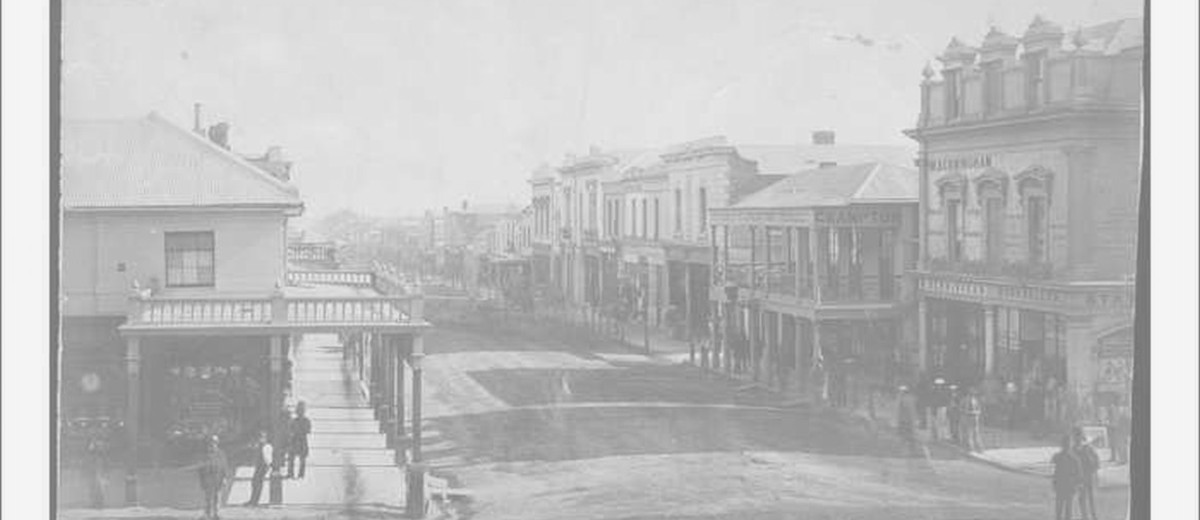

Add mediaHindley Street

Images

Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia, SLSA: B 1892/1, http://images.slsa.sa.gov.au/mpcimg/02000/B1892_1.htm, Public Domain

Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia, SLSA: B 3645, http://images.slsa.sa.gov.au/mpcimg/03750/B3645.htm, Public Domain

CommentAdd new comment

Quickly, it's still quiet here; be the first to have your say!