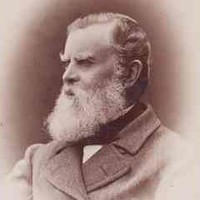

Person

ContributeShortly before his death on New Year’s Day, 1887, Walter Watson Hughes wrote to his nephew, ‘I have been a sinner all my life.’ Enigmatic words indeed for someone involved in the saga that surrounded the legal ownership of the Moonta Mine. In a dispute that raged between 1861 and 1870, he and four co-owners were accused of fraud. The Moonta Mine was worth fighting for, as it proved to be the first South Australian company to generate a million pounds in dividends.

Walter Watson Hughes was born in Pittenweem, Fife, Scotland, on 22nd August 1803, the son of Thomas Hughes and his wife Eliza (née Anderson). He went to sea at an early age with lofty ambitions. An obscure Scottish publication contains a quote from a letter he wrote to his father: ‘I sling my hammock in the forecastle, but I am resolved to spread my cot in the cabin.’ True to his words he became master of the brig Hero and traded in opium in the Indian and China seas in the 1830s. In November 1839 he came to Adelaide and on 21st September 1841 married Sophia Richman. Three years later he became a sheepfarmer on Yorke Peninsula.

When Hughes first found traces of copper on his pastoral run in the early 1850s, he was short of funds and simply sat on his find while nurturing a valuable relationship with Edward Stirling, one of four directors in Elder, Stirling & Co. When his shepherd, James Boor, found copper on Hughes’ Wallaroo property in December 1859, Stirling and his brother-in-law, John Taylor, invested in the venture. Six months later, when all three faced insolvency, Stirling and Taylor tried to resign from the company and take half the company assets with them. Robert Barr Smith got wind of their plans and called their bluff. In a smart move, he and Thomas Elder also became partners in the mines.

It was then that Patrick Ryan, another shepherd of Hughes, found copper at Tiparra Springs in May 1861. Lodging claims for this site, which became the Moonta Mine, was not straightforward for Hughes. With grievances against Hughes, Ryan tried to take out the claim with other friends, who became known as the Mills Syndicate. When their application was botched by Ryan and rejected by the Land Office, Hughes made the claim on behalf of Ryan and for the four partners of Elder, Stirling & Co. His interference was condemned by the Mills Syndicate as a blatant abuse of the mining regulations and protests by them and others saw a select inquiry, a Supreme Court case, an equity case in the Supreme Court and the first Privy Council judgement for South Australia. But when funds ran out in 1868, the Mills syndicate settled out of court for £8,000, leaving Hughes and his partners owners of the Moonta Mine. ‘Technical errors’ in Hughes’ mineral claims were sanctioned retrospectively by the Mineral Lease Validation Act of January 1869.

In the early 1860s Hughes established Hughes Park station at Watervale in the mid-north and over the next few years acquired other large pastoral properties. In 1872 he promised £20,000 to endow two professorships, in classics and philosophy, at the proposed University of Adelaide. When the Universty Association asked him to modify the terms of the deed so that the money was not tied to these chairs, Hughes threatened to cancel the gift. The deed eventually went through, an Act of Incorporation was passed in 1874 and Hughes’ contribution inspired others, including another £20,000 from Thomas Elder. For this reason, Hughes became known as the ‘Father of the University’.

In 1864-70 he lived in England and retired there permanently in 1873, taking up residence at Fan Court, Chertsey, Surrey. In 1880 he was knighted for his services to South Australia. He died on 1st January 1887 and was buried in the village churchyard of Lyne, near Chertsey. In 1906 a bronze statue of him, sculpted by Francis Williamson, was erected in front of the Mitchell Building of the University of Adelaide on North Terrace.

Media

Add mediaImages

Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia, SLSA: B 55265, http://images.slsa.sa.gov.au/mpcimg/55500/B55265.htm, Public Domain

Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia, SLSA: B 26275, Public Domain

CommentAdd new comment

Quickly, it's still quiet here; be the first to have your say!